Notes on Sailing Small Schooners

This is about how to sail schooners. Small schooners, mostly gaffers. They represent my opinion, which was developed sailing several kinds of rigs, mostly small schooners. I wrote them becuase I remember how much learning I had to do when I got my first schooner (I'd sailed schooners and brigantines before that, but had mostly sailed sloops), and how much I wanted instructions then.

These notes are intended for people who know how to sail, but are not that familiar with schooners. This is not an introduction to gaff rigs (Tom Cunliffe's book, Hand, Reef & Steer is highly recommended for those unfamiliar with gaffers).

Not everyone who sails schooners will agree with all these points. Different vessels have different characteristics. Different experiences will influence opinions, and what I've written is what works for me on the vessels I've sailed. Most of my sailing has been done either singlehanded or with one-person watches--where each person needs to be able to raise, lower and reef all sails by themselves. So these notes are oriented towards sailing schooners alone or with small crews.

Comments and suggestions are welcomed (see the contact link at the bottom of the page).

- Differences between schooners and other rigs

- Setting Sails

- Order of Raising and Lowering Sails

- The Fisherman

- Gaff Topsail

- Tacking

- Heaving To

- Anchoring

- Storm Sails

- Contact

Differences between schooners and other rigs

The biggest difference I find in sailing schooners versus other rigs is the big effect the mainsail has on steering. Because the mainsail is so far aft on a schooner, it pushes the stern around a lot, and how the main is sheeted in and reefed has a big effect on which way the boat will want to turn. The more wind, the more force the mainsail exerts on pushing the stern to leeward. Any time you want to change course, you need to think about the mainsail. If you want to bear off, often you will need to ease the main sheets to do so, and if you want to head up, it will be much easier to do so if the main is sheeted in more.

How much an effect the mainsail has on bearing a particular schooner off does depend on the keel shape, relative rudder size and position, and relative size and position (how far aft) of the mainsail. Schooners may not bear off without easing the main sheets and/or reducing the size of the mainsail. Reducing the size of the mainsail quickly can be done with gaff sails by scandalizing (quickly easing the peak halyard a lot to spill the wind out of the sail). Letting go the halyard on a Bermudian main gives a similar effect if the sail falls down (or can be quickly hauled down) far enough.

I recall a pleasant evening sail in the gaff-schooner Rosemary Ruth, approaching the shore on a beam reach, just downwind of the last of the moored boats in the marina I kept her in, I tried to bear off to gybe and the mainsheets jammed. I don't remember now why the sheets jammed, but there I was, heading straight for the shore, with no room to head up and tack because of the moored boats just upwind, and unable to bear off and gybe with the jammed mainsheets! We quickly eased the mainsail peak halyard to scandalize the mainsail, which allowed the boat to bear off and gybe in time to avoid the shore. I thought about how silly it would have looked to run aground in ideal sailing conditions, beside a popular walking path, right outside my marina! Be certain you have a way of being able to bear off quickly.

Similar to other mult-masted rigs, it is very important to keep the slots open between the sails. Going aft, the air flow needs to be directed such that it helps the next sail farther aft as much as possible. It is difficult to be specific on this, as schooner rigs vary so much, but, for example, using a gaff vang on the foresail to control the twist of the foresail so it doesn't sag off too much will help the mainsail get more drive. Look for an even flow of air across all the sails from top to bottom. Sewing (or glueing) tell-tales onto the sails helps a lot.

Setting sails:

One of the nice things about sailing small schooners, is that the sails are small enough to be raised by one person.

I made a short video about raising sails on the small, Tom Colvin designed, gaff-rigged schooner Doxy at Raising Sails on a Gaff-rigged Schooner. The Schooner Issuma YouTube Channel is a good source of information about voyaging schooners, and worth subscribing to.

Below, in pictures, the foresail is being raised on Rosemary Ruth on a chilly spring day in New York:

|

Taking off the sail ties. | ||

|

Checking halyards are free | ||

|

Haul both throat and peak halyards at the same time | ||

|

Keep the gaff roughly horizontal | ||

|

At this point, the throat is mostly up, and it is time to handle the halyards one at a time | ||

|

Make down the peak halyard temporarily and horse (swig) in the throat halyard all the way. After the throat halyard is made down, raise the peak halyard the rest of the way and make it down. |

Order of Raising and Lowering Sails:

I generally disagree with the idea that one should turn into the wind to raise or lower sails on a schooner. Its fine on a little sloop to luff up and raise or lower sails. On a larger boat, with more sails, going into the wind to raise or lower sails means sheeting in a lot of sails to head up, and then easing them off again later. .

Turning the boat into the wind to raise or lower sail is ok in calm seas, but not what you want to be doing if you are in a small vessel in moderate (or higher) seas, or if you are sailing without an engine. All the boats I have ever sailed long distances on have been capable of raising and lowering their sails on any point of sail.

The objective of raising and lowering sails in this order is to begin sailing on the desired course as soon as possible.

The foresail is generally the first sail up and the last sail down, because the boat is pretty much balanced with foresail alone, on any point of sail. Generally, to reduce sail, you want to douse the highest sails first, then the ones at the ends of the boat, and lastly the lower sails amidships. With a long, drawn-out sail plan like schooners have, the sails at the ends of the boat have a big influence on the direction the boat will want to go.

These comments apply to a small gaff-rigged schooner, with a jib and forestaysail, a fisherman and main topsail, no fore topsail. Similar procedures apply if there is no forestaysail (just a jib), or if using a gollywobbler instead of a fisherman.

If the desired course is on the wind, you want some sail aft to keep the boat pointing, so this is the order to set sails in (douse them in the reverse order):

- Foresail

- Main or forestaysail

- Jib

- Fisherman or Main topsail

As the wind picks up and the boat heels, the shape of the leeward side of the hull (the side that is fully in the water when heeled) will make the boat want to turn into the wind. So when reducing sail on the wind, you want to reduce heel (ie get down the fisherman and main gaff topsail), and reduce the amount of sail aft that is also acting to turn the boat into the wind (ie, reef the main, douse the main gaff topsail).

Off the wind, where you want to maximize sail area forward, to keep the boat from heading up into the wind, the order to set sails in would generally be (douse them in the reverse order):

- Foresail

- Forestaysail

- Jib (the order of the first three varies)

- main or fisherman

- Main topsail

I often sail off the wind with a fisherman or spinnaker set and either no mainsail or a reefed mainsail. This reduces weather helm.

A larger schooner (with enough crew) may want to raise the main first, because raising it will head the boat towards the wind and it is easier to raise the sail the closer to the wind it is (the larger the sail, or the more problems it has with friction, the more you care about the force involved to raise or lower it), and to keep the boat head-to-wind to make the other sails easier to raise.

The above method has worked well for me, on the vessels I've sailed on. I received an interesting note from Thomas Church, who has been sailing an Alden 'Nor'wester' schooner extensively for many years. Thomas describes sailing a schooner that balances much differently than what I am used to:

I presently own a 1926 alden schooner "nor'wester" which is basically the same as built. The nor'wester sails very poorly with only the for'sle and only down wind which makes it almost impossible to raise the main in any kind of wind.

In any wind the first sail up and last sail down is always the main. In high winds the main is reefed as needed and forc'l dropped first, then the jib, and finally the main. The main is raised first then the jib and finally the forc'le. She sails very well under reefed main alone but only goes down wind without at least some of the main up.

So I have to qualify the instructions I've written by emphasizing that they are for a schooner that balances on all points of sail under foresail alone. I am not used to schooners that can sail well under main alone--I am used to schooners that have lots of weather helm under main alone.

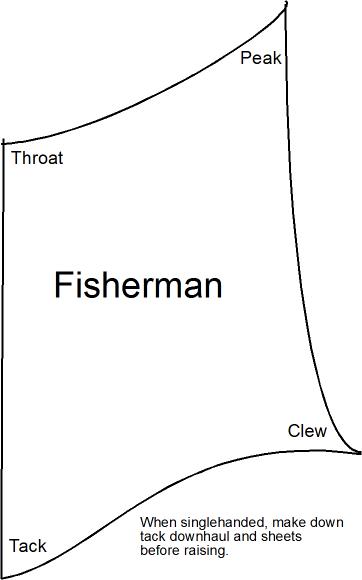

Fisherman:

Controlling the leading edge of the fisherman by putting it on a track on the aft side of the foremast makes the sail much easier to deal with.

Make sure you can get the fisherman down quickly if the wind suddenly picks up.

Many schooners cannot tack (or gybe) the fisherman while it is set. This is because of spring stays, or other stays between the masts preventing tacking the fisherman while it is set. To tack/ gybe, they need to drop the fisherman, tack/gybe the boat, then bend the sail on the other side and set it again.

Schooners that have no spring (or other) stays between the masts interfering with tacking, tend to use the fisherman more in coastal and harbor sailing, since it is much easier to tack/gybe. Two sheets are used if the sail is to be tacked while set. I like to use polyethylene or polypropylene rope for fisherman sheets because the rope can be large enough diameter to be easy to grip, and still light enough to not interfere with the sail shape in very light winds.

Fisherman on staysail schooner Shearwater in New York.

Staysail schooners tend not to have any difficulties tacking the fisherman, which is set above and forward of the main staysail.

Fisherman on staysail

schooner Issuma in Brazil. Odd shape of this fisherman results from it

originally being cut for a roller-reefing system.

On schooners where tacking the fisherman is not possible, whether it is better to set the fisherman to windward or leeward of the foresail depends. I usually set the fisherman to leeward of the foresail.

Generally I find the fisherman sets better to leeward of the foresail, though this does depend on where the tack downhaul is made down. The amount of control over foresail peak sag (ie, whether or not you are using a gaff vang) also matters, as you do not want the foresail peak to chafe the fisherman (at least not if you are making long voyages).

Fisherman set to windward of foresail

Fisherman set to leeward of foresail

Lowering the fisherman is easier if it is done to windward of the foresail. That way, the wind blows it into the foresail, instead of out beside the boat, and it is much easier to gather in and keep it out of the water.

Fisherman sheeting points vary with the boat, and sometimes the conditions. Off the wind, it may be best to sheet the fisherman through a block on the main boom so the sail is somewhat poled out..

Once set, the fisherman is trimmed by a combination of both the sheet (mostly) and the peak halyard. The closer to the wind, the more you want to peak up the fisherman, the farther off the wind, the more you want to ease the peak to let it move forward to put more belly in the sail. Sometimes you may want to adjust the luff tension with the tack downhaul. The objective is to have no creases in the sail, a taut luff if going to windward, no chafe against the foresail gaff (or anywhere else), and a smooth flow of air over the sail. Like other sails, it helps to have telltales attached to help see how it is setting.

Gollywobblers (at least the only kind I've used) are just used like large fisherman sails.

Short-handed fisherman setting:

Mark (marker pen will last a while, a whipping is better) the sheet(s) and tack downhaul at the approximate place where they should be when the sail is set

Make down the (lee) sheet and tack downhaul in their marked positions..

If you can't make down the sheet and tack downhaul in their approximately correct places before raising the sail, a one-person task can become a three-person task....

Here, the sheet has been marked with marker pen and made down.

Feel around each edge of the sail to ensure it will not tangle

Either hoist the throat and peak halyards together, or alternately hoist some throat, then some peak.

Here, on the staysail schooner Issuma, the throat halyard is being hauled. The peak halyard is temporarily cleated on the cleat under the mast winch.

Keep looking aloft to see that the halyards and sail are not snagging anything.

, the throat halyard has been hauled up more and the peak halyard has gone loose.

Here, the throat halyard has been temporarily made down, and the peak halyard is now being raised.

Too much slack in the peak halyard would result in it snagging a spreader on this schooner.

Get the throat up all the way before you get the peak up all the way.

.

Here, both halyards are up all the way. The creases seen running from the peak will go away when the sheet is tightened (if not, then the sail needs to be peaked up a bit more).

Off the wind, the peak may not be raised as high (to make the sail shape more curved), as when sailing on the wind.

Halyards up, sail sheeted in.

This isn't a good sail trim picture because it is very light air with a heavy (9oz sailcloth) sail with chafe marks making the curve of the sail quite difficult to see.

It is also an unusually shaped fisherman sail, because it was originally cut to work with a roller-furler and later modified to have the luff set on a track ..

Adjust the tack downhaul if necessary (you can pull it down to tighten the luff).

Coil the lines and make sure you are able to quickly let go the halyards (I coil them in figure-8s on deck) to get the sail down in a hurry if necessary.

Gaff topsail:

Another great light-air sail. Usefulness depends on how large it is (or they are) relative to the lower sails. To simplify setting it, mark the tack downhaul at the approximate position where it will be made down so you can make it down first, then raise the halyard, then sheet the sail in. While raising the halyard, keep an eye on the loose sheet--if it looks like it may catch on something, periodically take the slack out of it.

Gaff topsail (dark colored sail above mainsail) on the (not small) schooner Pioneer. Topsail sets to windward of the gaff halyards on one tack, and to leeward on the other...I've never seen anyone bother to douse and re-set a topsail when tacking.

Tacking:

In light air, with a full-length keel, it is often necessary to back the jib (or forestaysail) to complete a tack. In really light winds, you may also need to back the main to head far enough into the wind at the start of the tack.

On a boat with a jib which is tacked manually (not self-tending), backing the jib is simple -- leave the sheet made down until the other sails are filling on the new tack.

On boats with self-tending jibs, a tail rope can be used. This is a (relatively) light line attached to the jib (or staysail) boom, and run aft. Before tacking, take up the slack in the tail rope and make it down. After the other sails are across, release the tail rope and sheet in the jib (or staysail) on the new tack. Of course, if you are fortunate enough to be sailing with crew, they can just go forward and hold the staysail to windward for the tack.

The schooners I've sailed were usually unable to tack in conditions windy enough to not have a headsail (jib or forestaysail) set--the waves associated with the windy conditions were likely to stop the boat before a tack could be completed. So, when it was windy enough to not have a headsail set (windy enough that the main would be either reefed or not set), I'd wear ship (bear off, gybe and head back up on the opposite tack) instead of tacking.

Anchoring:

Anchoring uunder sail is a maneuver that is easy with a schooner (though not in a crowded anchorage). I will only describe one way of doing it, there are other ways.

This way assumes that the boat will lie to the wind, not the current, and that you intend to roughly stop where you want to place the hook, then back down on it.

Approaching the desired area, consider dropping the foresail (definitely get the fisherman down) to reduce speed.

When ready to head into the wind, sheet the main in tight and drop the jib (possibly the staysail as well). The big main will keep the boat heading into the wind, and you can calmly lower the anchor when the boat stops making headway over the ground.

After the anchor seems set, overhaul the main sheets and use the preventer to back the main so you can sail down (backwards) and confirm the anchor is set.

Heaving to:

Heaving to can be done with the foresail (reefed or not) on gaffers, or with a storm trysail on the mainmast, in moderate or heavy winds.

Heaving to in light winds may not be as simple as it is on a sloop--tack the boat while leaving the jib sheet cleated and the now-backed jib counteracts the main. On a schooner, the foresail and mainsail may overpower the backed jib and keep moving the boat forward. The main or foresail may need to be eased, scandalized or doused to heave to in light winds.

Storm Sails:

I've had storm sails made for all the schooners I've owned. For the gaffers, I had both storm jibs and storm trysails made. For the staysail schooner, I had a storm jib made, and rely on a triple-reefed main, made of polyester and spectra (if it wasn't such a strongly-built sail, I'd get a storm trysail).

The foresail on a gaff schooner is a great, "built-in" storm sail, and may be quite suitable by itself if in good condition. If you are not planning on sailing much in heavy weather, then the gaff foresail may be all you need, however, if a gaff jaw breaks, or the foresail rips/blows out, it can be very nice to have other options.

If you have a sailplan where the designer has already drawn in storm sails, so you don't have to size them, that's great.

For the gaff schooners, I found that the way to size the storm jib is to try and get the biggest one that can fit in the foretriangle, without requiring going out on the bowsprit to set or douse it (the bowsprit being the last place you want to be at sea when the wind picks up). This is opposite to how storm jibs are recommended to be sized for bermudian sloops, which have large foretriangles capable of setting far more sail than is desirable when it is really windy. On gaff schooners, the foretriangle tends to be quite small, especially when not using the bowsprit, so you end up with a pretty small storm jib.

I sized the storm trysails for the gaff schooners partly by keeping them small enough to be able to be set on either the mainmast or the foremast. Normally, the trysail would go on the mainmast in place of the mainsail, but in the case of a damaged foresail or foresail gaff, I wanted to be able to set the trysail off the foremast also. Most of the sizing for the storm trysails was done by guessing what would balance the storm jib, after sailing with a deeply-reefed mainsail, and, once, sailing with a small sail borrowed from another boat, set flying, in place of the mainsail.

You can make storm trysails with a small gaff, to increase the area and bring the center of effort a bit further aft, but I've never done so.

On the used sail market, there are many storm jibs available. I've found that these tend to be constructed to meet race regulations, not to really be used frequently (they are too lightly-constructed for extensive heavy-weather use). I've always had storm sails built to my specifications, though this is costly, but results in something that really works.

| Contact | Home | Issuma | Orbit II | Rosemary Ruth | Presentations | Videos |